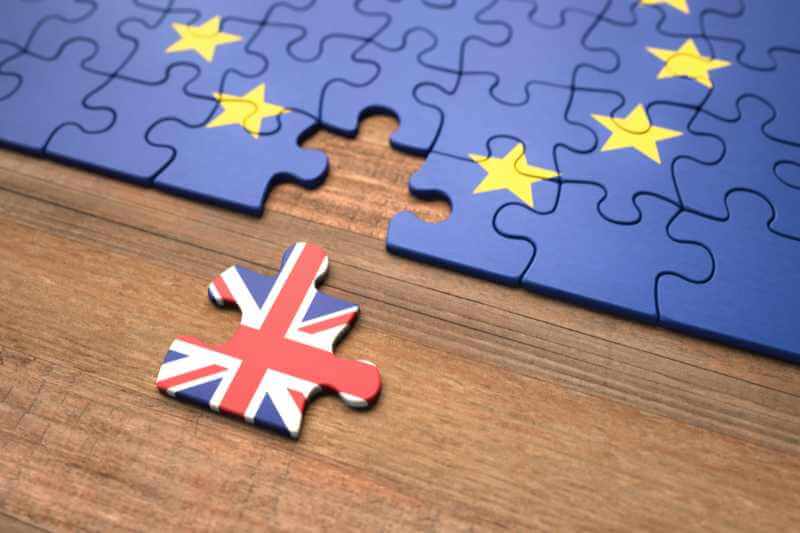

It is more than three years after Britain’s exit (Brexit) from the European Union and many British citizens are still confused as to why the split occurred and whether or not it was a beneficial move. The referendum on whether to remain a member or leave the EU was held in June of 2016 and it was a close call as 51.9% voted in favour of leaving with 48.1% wishing to retain EU membership.

In March 2017, British Prime Minister Theresa May officially notified the European Union Commission of Britain’s withdrawal, and Brexit negotiations got underway with the aim of making the process as smooth as possible. The end of March 2019 was the proposed date of withdrawal, but this was delayed due to the British general election in June 2017. The unstable situation in the British government delayed the implementation of Article 50, the EU guidelines applicable to countries wishing to withdraw voluntarily from EU membership.

EU Membership Dissatisfaction

The United Kingdom first joined the EU in 1973 (then called the European Communities or EC), and even though there were tremendous economic benefits to membership, not all British citizens were happy with the situation. England, in particular, valued its sovereign state standing and viewed membership of the EU as ceding power and authority to a foreign body.

Even from the beginning, British citizens were unwilling to change their currency unit from the pound sterling to the euro and opted out of this membership clause. Retaining its own currency afforded the UK a measure of economic sovereignty, but there was still a number of eurosceptics who wanted nothing more than to leave the EU as soon as possible.

A 1975 referendum on whether the UK should remain in the EU or not was supported by just over 67% of the voters. However, the fact that almost a third of the electorate were against membership was already causing cause for concern both within the British government and at EU headquarters.

Perhaps because of concerns over the rising anti-EU sentiment across the United Kingdom, no further referendums were held for the next forty years until pressure from eurosceptic Conservative Party members, as well as from UKIP (UK Independence Party), forced Prime Minister David Cameron to guarantee a public referendum on EU membership should his Conservative Party be re-elected.

To the surprise of many, Cameron and the Conservatives won the 2015 general election (albeit by a very small margin), and the EU referendum was scheduled for June the following year. Britain’s potential exit from the EU was quickly dubbed Brexit, and a period of heavy campaigning by the Yes and No proponents ensued over the months before polling day.

Right up to the last, the outcome of the Brexit vote remained undecided, with both camps expressing confidence their side would win. The vast majority of English citizens were in favour of leaving, but (perhaps because of the diversity of the capital city) the greater London area voted to retain EU membership. Wales also delivered a no vote, but Scotland and Northern Ireland were firmly for remaining in the EU family.

The vote was close, but a narrow majority carried the day. Prime Minister Cameron resigned, and Britain was on its way out of the European Union. The next step was to meet the conditions laid out in Article 50, which would entail four long years of negotiations.

Arguments for Brexit

The Brexit referendum was supposed to show the anti-EU factions in the Conservative Party and elsewhere that the United Kingdom electorate was firmly in favour of remaining in the European Union. Conceived by the Prime Minister of the day, David Cameron, a resounding affirmation of EU membership was expected. This, however, turned out not to be the case, as Cameron had seriously misjudged the amount of public support for breaking with the European Union.

Anti-EU sentiment had been building across the UK for decades and the Brexit referendum finally gave the dissatisfied members of the public the opportunity to express their discontent. Those in favour of Brexit listed a number of factors for opting out of EU membership and among the most significant were economic issues, rising immigration and politics.

Economic Issues

Although a number of Brexit advocates (dubbed Brexiteers) regarded the EU as being economically advantageous to Britain, the majority considered EU regulations as restrictive and an imposition on market freedom. Leading Brexiteers like UKIP leader Nigel Farage believed that leaving the EU would allow the UK to open free trade negotiations with non-EU countries such as the United States.

These new trade deals would be to Britain’s advantage and aid in a much-needed economic recovery following the British financial crisis of 2008 and a similar crisis across the EU a year later.

As a member of the EU, Britain’s economy was closely tied to that of the EU, and if Europe was struggling, that had a negative effect on Britain. In Britain, the austerity reforms of 2010 also caused dissent among the public as they experienced significant cuts to public services and welfare payments.

Rising Immigration

Even before the UK joined the EU the subject of immigration had been a contentious matter. Following World War II, Britain experienced a significant surge in the number of immigrants arriving and many Britons were concerned about the ever-increasing numbers.

Statistics show that 201,000 EU citizens migrated to the UK in 2013 and this number increased to 268,000 the following year. These EU citizens were legally entitled to relocate to the UK just as British nationals were at liberty to reside and work in any of the other EU member states. This fact, however, did not appease those who regarded the numbers as being far too high.

In 2015, around 170,000 migrants arrived in the UK from other EU member states while a further 190,000 immigrants came from countries outside the European Union.

A small poll of 12,000 voters on referendum day revealed that around a third of the Brexit supporters were voting to leave the EU due to concerns over border security and were of the opinion that the flow of immigrants could best be controlled if the UK was in charge of its own borders.

Data provided by the University of Oxford also recorded that reducing immigration and strengthening border control was the most important reason for a YES vote for approximately 56% of pro-Brexit voters.

In an article on Brexit, British weekly publication “The Economist” noted that areas of Britain that registered significant increases in migrant numbers were much more likely to vote in favour of leaving the EU for almost 94% of those people who intended to vote.

Another factor in the growing support for Brexit was the accession of several East European countries to the EU. These were mainly poor countries with comparatively low standards of living, and the nationals from these countries were quick to move to the UK for a better life. The significant number of Eastern Europeans arriving added to concerns over immigration levels, and many Britons added their support to UKIP and rallied behind its leader, Nigel Farage.

Politics and Policy

In 2017, former U.S. President Trump described Germany’s decision to admit over a million illegal immigrants as a “catastrophic mistake” and this view was supported by UKIP. The flow of illegal immigrants was not confined to Germany as the new arrivals quickly dispersed across Europe with the United Kingdom the preferred destination for many.

As part of the EU there was little or no control over who entered the United Kingdom from a fellow EU member state and the number of migrants (legal and illegal) arriving on British territory rapidly grew. The UK, as a member of the European Union, was subject to European laws and rules and could not deny entry to the arriving migrants.

Those who wished to remain in the EU were quick to dub the Brexiteers as racists, but while this may have been true of some, for the vast majority, it was a matter of national security and putting Britons first.

Leaving the EU would mean that the UK would no longer have to follow EU rules and could implement its own policies regarding immigrants and immigration.

British Sovereignty

The British are a proud race and not given to taking orders from foreigners. Being subject to the EU rules and laws from bureaucrats in Brussels was unacceptable to many British citizens from the outset and this resentment only grew with the passage of time.

For these UK citizens, Brexit signalled the end of European control over British affairs and a return to the days of British sovereignty. Taking control of the UK borders has already begun with the British government’s introduction of the UK Nationality and Borders Act in 2022 and the planned introduction of the UK ETA (Electronic Travel Authorisation) in late 2023.